Of course Violet couldn’t sleep that night either. She lay awake listening to her brother snore and stared up at the darkness. She was so excited about getting into the veterinary college. Everything she had dreamed for her life was coming true, everything she had promised her father at his graveside that she would do: that she would become a veterinarian, practice in Beringford, make a good living and support her mother back in the village. She pictured him ruffling her hair as he used to, as Bertie would do sometimes now. She saw his beard bristle up at the edges as he beamed down at her. “That’s my lass,” he would say. How she missed him!

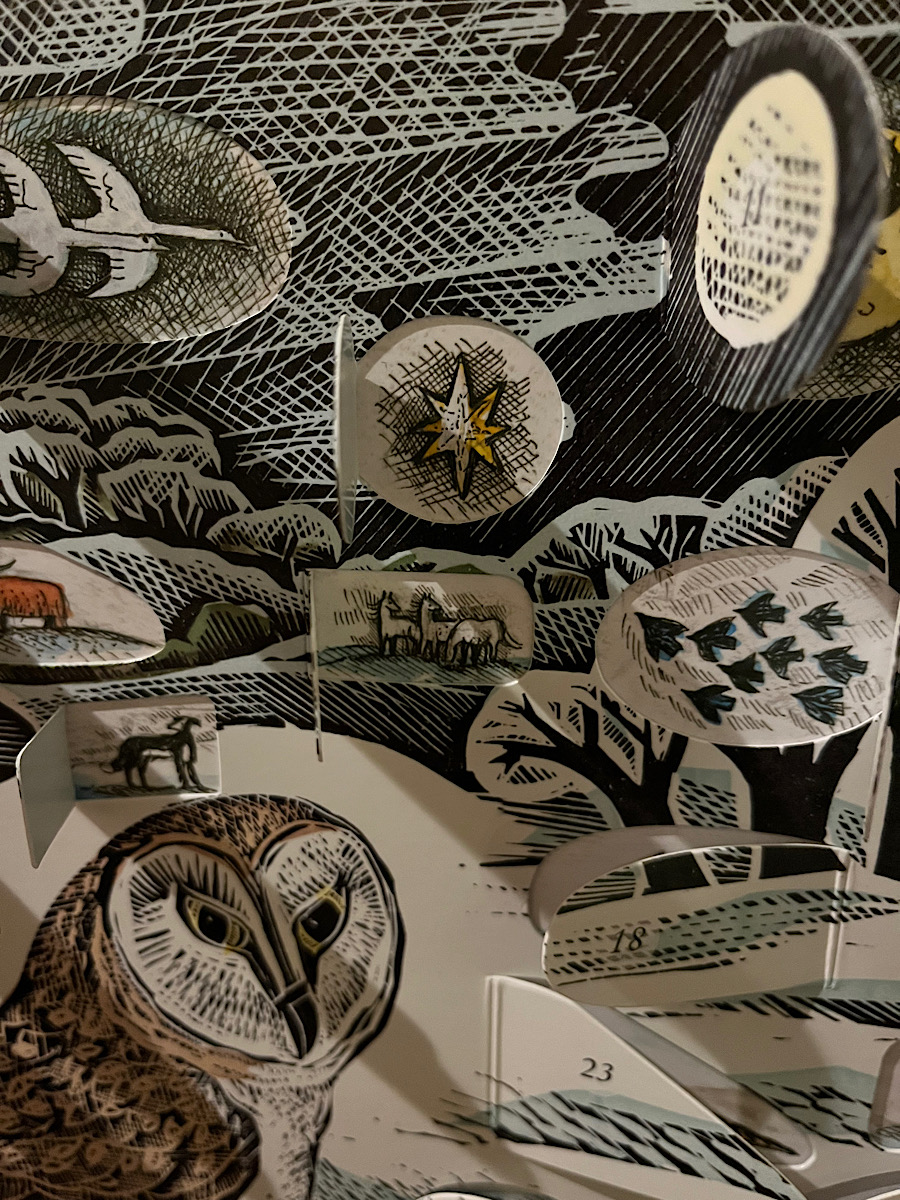

She rolled over in bed. She saw her life unspooling in Beringford: paved streets, coffee houses, chiming accents, concerts. So far from the mud ruts, smells, and bawdy jokes of the village. At the same time, the village was her father, in a way, and leaving it she knew would feel like leaving him behind for good. And then, in the owl’s baleful hoots, the falcon’s burning eyes, the squirrel’s drooping tassels, she could sense more than she could say what the civilization she yearned for was doing to the animals and the woods that she loved, that had made her want to become a vet in the first place. It was all so tangled up. It was all too much.

A dim point of light caught the corner of her eye, and she tossed back over to look out the window over her bed. An unusual star hung above the north wood, its light smeared out in long, bright rays across the old, warped panes. The star seemed to spin slowly, mesmerizing her. She felt her pulse slow, her mind relax. She thought: tomorrow, I’ll ride out to the north wood again, see how the squirrel is doing, and the owls. Then, miraculously, she fell asleep.