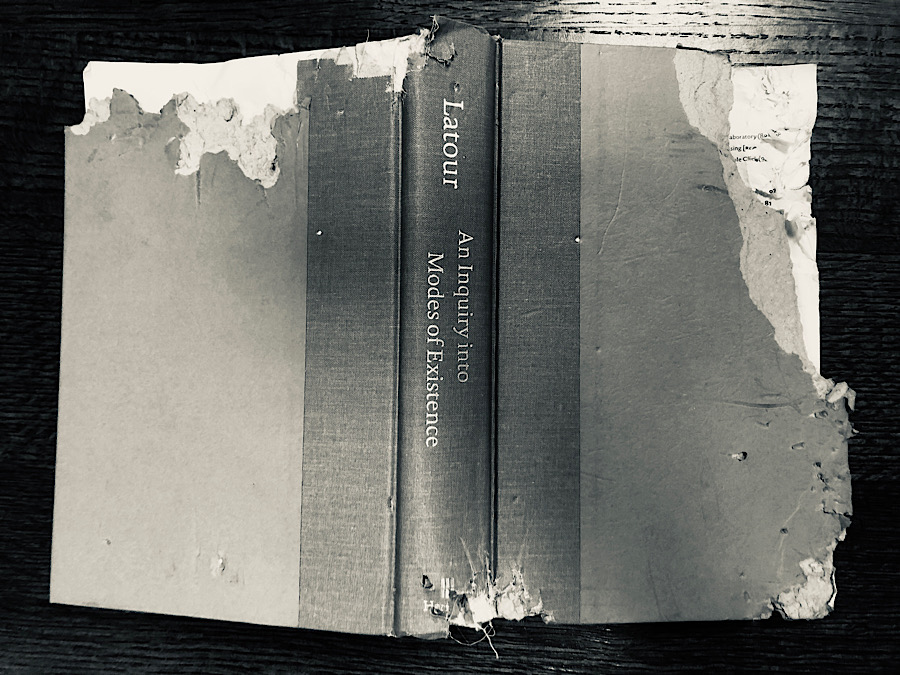

The first time I met Bruno Latour, I brought with me a copy of his newest book (at the time) An Inquiry into Modes of Existence. I had some questions for him about it, which he was generously willing to answer. There was just one problem: my dog Jasper had gotten hold of the book the night before I flew out for Paris and chewed off several corners pretty substantially, as well as ripping out part of the back matter.* I had no time to replace the book and knew there was no chance of pushing back this meeting given Latour’s schedule. So, there in the office of the most famous person in the world in my field, I had to pull out a quite literally dog-eaten copy of his most recent book and flip through to the passages I had questions about.

Bruno was–and I think this says a lot about what sort of person he was–charmed and delighted by Jasper’s handiwork (dental work?). He made his assistant snap pictures for the AIME blog. He cracked a joke about the book being hard to digest. And all this after we’d miscommunicated about our meeting spot (my fault) and he’d still waited around at his offices on the Boulevard St Germain after his day was done to squeeze me in. I’ve been ghosted for a lot less by scholars whose CVs would fit inside Bruno’s five times with room left over. But in the years and emails and interviews that followed, he never treated me with anything short of the same gracious good humor. This was the second lesson I learned from Bruno Latour: you’re never too big for manners.

The first lesson I learned from him was how the world worked–at least our modern world. His long essay We Have Never Been Modern was my Rosetta stone in graduate school, making so many puzzling pieces about how science and religion interact in our world snap into place. (If you’re interested in reading that book, you should; and if you need some context for it, the guys at Partially Examined Life and I broke it down in a podcast.)

The third lesson I learned from Bruno followed on this lesson, and that was that a religious background–indeed, a full-blown faith in God–didn’t disqualify you from studying how science works in our world. On the contrary, it uniquely positioned you to notice and ask tough questions about the important roles that faith and trust play in the making of scientific knowledge. Latour was a lifelong, devout Catholic. He seriously contemplated becoming a priest before he trained as an anthropologist, and that openness to different ways of accessing truths about the world made him a good listener and a better scholar. When his participants in the West African fieldwork that formed the basis of his thesis told him that this or that god, this or that force, made them act in a certain way, he didn’t dismiss those leads out of hand because they didn’t match up with his Western academic preconceptions. Rather, he listened, he asked questions; he followed hints. Doing so led him to important insights into the ways all of us put our trust in a motley crew of “idols,” counting on them to tell us about the world when we don’t have the time or resources or expertise to go figure it out for ourselves.

Not only did Bruno never hesitate to put his faith in conversation with his scholarly work, he openly let it lead him to groundbreaking conclusions about the relationship of science and religion, about the ways in which our earth resists us and speaks back to us through climate change. He wove biblical analogies through all of his writings–casting his conversion to philosophy on the road to Gray in the same terms as St. Paul’s conversion to Christianity; talking about scientists wrestling with reality the way Jacob wrestled the Angel. At the same time, he never succumbed to the temptation to read the world through the Word, as so many Christian scholars before him have done. He rejected pat answers. He listened; he struggled; he changed his mind, long after he stopped needing to do so.

One of my favorite quotes of Bruno’s is from the Pasteurization of France, when he writes, “What resists trials is real” (158). It’s the easiest and best way I can define reality for my students: I quoted Bruno just last week, in fact, thumping my hand on the table in our classroom in a gesture that he gently mocks in Pasteurization as a naïve version of plural ontology. But it’s just when we bump up against miscommunications like this (or tables) that we learn where our ideas stop and the world starts, where we end and other beings begin. Bruno never shied away from those moments of resistance; he held on tight to the end, no matter how much reality thrashed around or wounded his pride.

And that’s why, when I got the news yesterday that he had passed away on Monday after his long battle with pancreatic cancer, my first feeling was honestly one of joy for him. Bruno devoted his whole life to chasing down the truth about the world with no fear of the tough questions and sometimes sharp criticism that came after him. Now, he’s finally getting to meet the Angel he wrestled with in the dark his whole life, face to face, in the light. I can’t imagine anything making him happier.

*The backstory there: Jasper, being enormous, had a few months prior successfully skifed off a table-top at my house a box of chocolates, which he very much enjoyed (and from which he apparently suffered no ill effects); the experience convinced him for quite a while afterward that any chocolate-box-adjacent object, including many hard-cover books, could also contain chocolate and should on those grounds be strip-searched.