Economy is the basis of society. When the economy is stable, society develops. The ideal economy combines the spiritual and material, and the best commodities to trade are sincerity and love.

Morihei Ueshiba, The Art of Peace

“‘So you see,’ [Diotima] said, ‘you are a person who does not consider Love to be a god.’

Plato, Symposium 202d-e

“‘What then,’ I asked, ‘can Love be? A mortal?’

“‘Anything but that.’

“‘Well what?’

“‘As I previously suggested, between a mortal and an immortal.’

“‘And what is that, Diotima?’

“‘A great spirit, Socrates: for the whole of the spiritual is between divine and mortal.’

“‘Possessing what power?’ I asked.

“‘Interpreting and transporting human things to the gods and divine things to men; entreaties and sacrifices from below, and ordinances and requitals from above: being midway between, it makes each to supplement the other, so that the whole is combined in one.

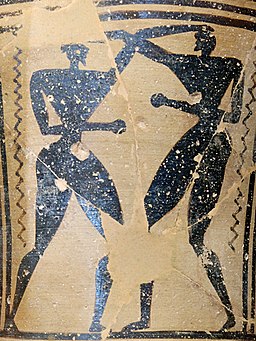

You might be wondering why this post is titled “Women” but begins with a quote about the economy. This turns out to be a really fascinating point of connection between the philosophies of O-Sensei and the Ancient Greeks. It Athens it wasn’t considered proper for women–at least the wives and daughters of landowning citizens–to be exposed to the rough-and-tumble atmosphere of the agora or public sphere. Their sphere was the private oikos or home compound. As a result of this segregation, Greek women were not generally recognized as rhetoricians. However, certain women are recorded in Ancient Athenian annals as having had a powerful indirect influence on the public sphere: these include Aspasia, Pericles’s partner; the Pythia, the oracle at Delphi; and, Diotima, one of Socrates’s teachers, whose philosophy of love he discusses at length in the Symposium.

How did these women influence the public sphere from their position in the private oikos? In part through the principle of oikonomos, the organization of the household, which lay under the purview of women and is also where we get our English word “economy.” Although the physical trading of goods in the agora was usually done by men, or female servants, the motivation and logic behind those trades came from the oikonomos–the storing, budgeting, and planning for production and profit-making supervised by the wives who oversaw the home estate while their husbands were off fighting on the battlefield, wrestling in the gymnasium, or strolling the shady stoa of the agora arguing about politics or philosophy. Little wonder, then, that when these men brought their friends home to continue the discussion over dinner, which they frequently did, that their wives added an acute economic perspective to the discussion–and public policy and philosophy changed as a result.

I’m not arguing that women were somehow separate but equal in Ancient Greece: they weren’t. They had no citizenship and no formal political rights. Neither is the world of aikido gender-balanced. In spite of the fact that O-Sensei always accepted women students, and there are several high-ranking female shihan in the federation, still in my dojo the men outnumber the women 5:1 at least; I’m often the only woman training when I go to class. And I don’t think my experience is terribly anomalous in the aikido world.

Yet, when I first thought about getting into martial arts and asked my friend Ed, who held black belts in multiple disciplines, which one I should try, he said without any hesitation, “Aikido.” His mother, born to a powerful branch of the Watanabe family in Japan, held a black belt in the discipline. So, he knew that the logic of aikido was very different from the logic of other martial arts. As I’ve mentioned before, aikido is a partnership, not a zero-sum game. It’s a conflict art whose goal is the end of conflict. If you “win,” if you dominate your “opponent,” you’re doing it wrong. The ultimate aim of aikido is love.

And love, Diotima tells us in terms I think O-Sensei would very much approve, is a special sort of economy–an exchange of request and reply, desire and fulfillment, material and spiritual that results in wholeness. Not profit, not excess, not bodies on the ground. Unity.

I don’t think there’s anything biological about women that necessarily makes us better suited to aikido or peacemaking. I do, however, think we have historically been put in a position that makes/lets us see power struggles from the outside. From this position, someone can perhaps find solutions to these struggles that those locked in their grip can’t: third ways, syntheses, harmonies. One of the men I train with in aikido told me he prefers training with women because with us “it’s not all about ego.” I don’t know about that. I do know that in aikido, I’m learning for the first time as a woman to own my space and my body and my boundaries, and to interact with others in a way that’s not fear-based. Maybe that’s the start of what Diotima and O-Sensei would call an economy of love.