…which is not at all in Athens, prompting some raised eyebrows from the guy at the Europcar rental counter: “You’re driving to Delphi and back? Today?” Yup. There was no way I was coming to Greece for the first time in my life and not going to Delphi.

I knew only the basic Wikipedia facts about the place until I got interested in it during my Ancient Greek Rhetoric seminar in grad school with Rosa Eberly. I think it was something about my crossover interests in science and prophecy at the time, coupled with the fact that Delphi kept coming up over and over again in the texts we were reading by Aristotle, Heraclitus, and other ancient authors. This made sense, of course. Delphi was to Ancient Greece what the Vatican was to Renaissance Europe: even if you didn’t believe what came out of the oracle, you had to work through, not around, its political power.

I ended up writing an article and a chapter of my second book on the rhetoric of the Delphic oracle: it was interesting to me not only because of what I mentioned above about its political power, and not only because of the similarities of that power to the power wielded by some scientific institutions in our late Modern era, but also because it’s one of the very few records we have of speeches given by a woman in Ancient Greece.

That woman was the Pythia, a middle-aged matron who served a term of roughly 15 years or so before being replaced by another channel for Apollo, whose temple was founded on the site of an ancient Gaian cult after he supposedly slew its namesake Python for abducting one too many local villagers. As legend had it, he stuffed its body in the ground and built his temple on top of it (insult added to injury?), and its rotting body (pythos means rotten, as in the English word “putrid”) exuded vapors that sent Apollo’s oracles into the trance via which they communicated the god’s will to supplicants. Interestingly, a series of geological surveys from the 1980s to 2000s found evidence of two young faults crossing directly under the temple site at Delphi; though the faults no longer opened at the surface due to earthquakes and sedimentation, probes drilled into them indicated the presence of ethylene gas, which can produce hallucinations (as in the ether used by old-time dentists).

Apollo’s oracle at Delphi operated from roughly 750 BC to 350 AD, when its decline in the wake of Constantine’s Christianization of the Greco-Roman world came to its natural end. From this period, we have a collection of slightly more 600 Delphic oracular pronouncements; given that the Pythia sat once a month for consultations, that’s probably only .5% of her total archive.

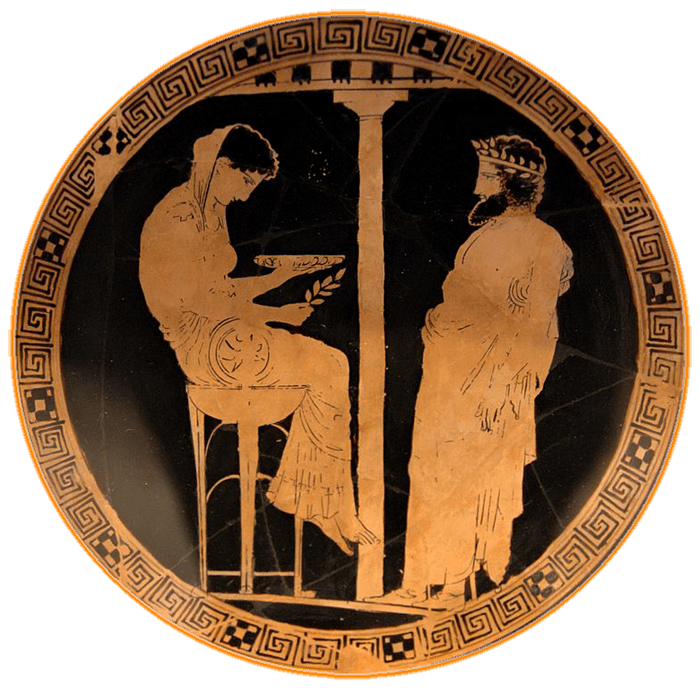

The vast majority of these pronouncements, however, were a fancy version of flipping a coin: the petitioner would ask a yes/no question, and the Pythia would draw either a black or a white stone/bean from a bowl to indicate Apollo’s response. Rarely did she speak: when she did, contrary to popular myths that she ranted and raved, eyewitness accounts indicate that she mostly spoke intelligibly in her own voice. Some of these responses were recorded in poetic hexameter; there, it’s unclear how much they were dressed up by the male prophetes who attended her as secretaries. Another category of responses were what are called amphiboles, meaning they had a double or open meaning and required discussion and interpretation before they could be applied to the situation at hand. One of the most famous of these was the “wooden wall” amphibole. Athens sent a theoros or messenger to Delphi in anticipation of (yet another) Persian invasion in late 481 or early 480 BC. The Pythia’s response was poetic and grim: Athens would be defeated, and the roof of the Parthenon would “run black with blood.” Understandably, the theoros requested a second word from Apollo; this time the god indicated that the city might be saved by a wooden wall. When this amphibole was debated back in the Assembly at Athens, many despaired at the prospect of erecting an enormous fence around the city with not nearly enough trees or time. But then the famous general Themistocles got up and said Apollo had meant for Athens to go out to meet the Persians on the sea in a naval battle–the sides of their ships would form the wooden wall that would repel the invaders. He ended up being right: Athens defeated the Persian navy soundly in the Battle of Salamis.

This story and others like it ended up shaping my conclusions about the special rhetoric of the Delphic oracle–that in the end, its purpose wasn’t so much telling the future as reminding Athens (and the other city-states who consulted it) of the values that held them together and made them unique, so they could make the choice that best reinforced those values and extend the special life of their polity into the future.

Obviously, Delphi holds a special place in my heart after all of this time I’ve spent with the Pythia and her words and history. Fortunately, Birgit and her colleague Sibylle were up for joining me for a day trip to the temple site. So, in spite of our Europcar agent’s doubts, we drove the 3 hours each way and still made it back in plenty of time for our flights.

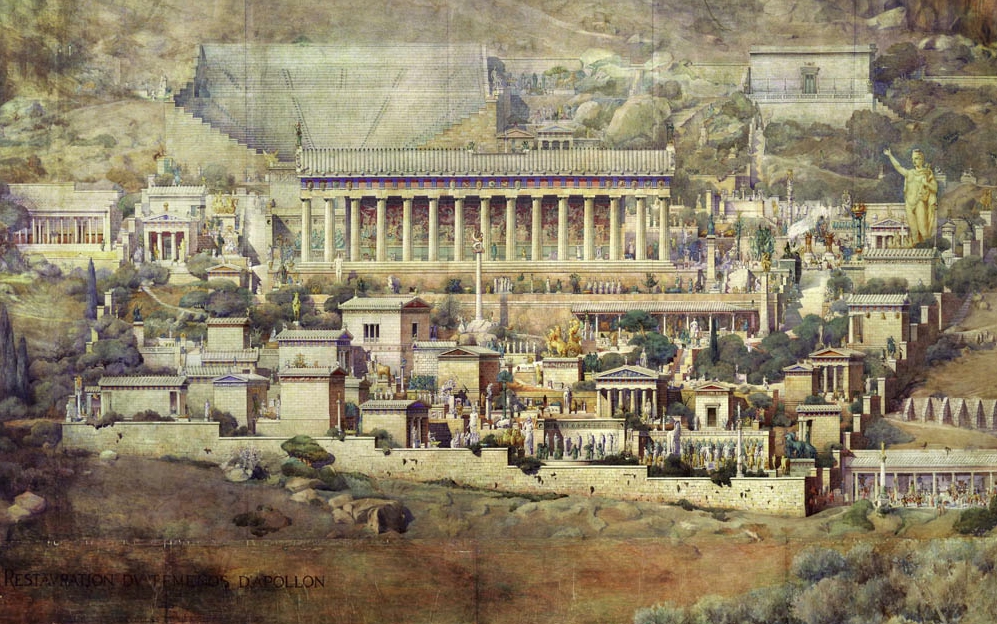

It really does help to think of Delphi as the Ancient Vatican–or, perhaps more accurately, Disneyland. Albert Tournaire’s 19th-century reconstruction above, though a bit fanciful, nonetheless does a good job of capturing its theme-park vibe. Shops lined the streets all the way to the temple, alongside shrines to associated gods like Dionysius and the Sibyl, gilded treasuries showing off the wealth of the member-states of the Amphictyonic League that supported Delphi’s upkeep, and scores upon scores of ornate votive statues and tripods donated by grateful petitioners. Every four years the Pythian games were held in the stadium and amphitheater perched above the Temple; in between there were various musical competitions and theater performances. In short, it was a circus. Today, the throngs of visiting tourists and highschoolers on their senior spring grips help keep the vibe going, though high up in the stadium, especially so early in the spring, it’s quiet enough to hear the bees buzzing in the yellow laurel flowers and the breezes–chilly from their run down Mt. Parnassus’s snowy flanks–soughing in the cypresses.

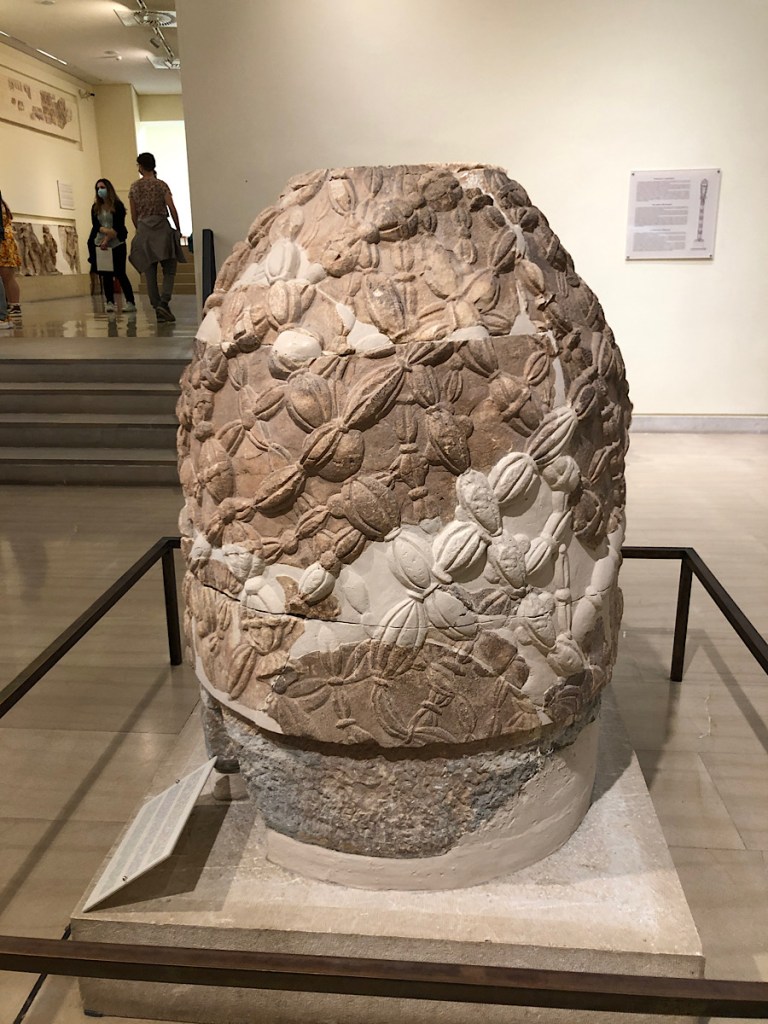

Sitting in that lofty spot and looking down at the ruins of Apollo’s temple, I wondered where the adyton was, the womb-like chamber in which the Pythia sat on her tripod, near the omphalos or navel stone, and gave her oracles; unlike at other Apolline temples, they haven’t conclusively located the space. I hoped that the Pythia sometimes had a chance to climb up out of that cave where everyone was high on power and fear and money and just sit in the sun like we were doing, listening to nothing more than the birds and the wind. Even if she and I don’t serve the same gods, I still have a lot of respect for her–for the generations upon generations of Pythias who dedicated the best part of their lives to helping their neighbors figure out how best to live in their chaotic world. In the end, the most helpful thing those petitioners probably learned at Delphi wasn’t anything the Pythia said to them, but rather the inscription they passed on their way to see her, chiseled into the lintel of the temple’s front door: gnōthi seauton. “Know thyself.”

Words to the wise.

2 thoughts on “Athens Day Five: Delphi”