The only cure for materialism is the cleansing of the six senses (eyes, ears, nose, tongue, body, and mind). If the senses are clogged, one’s perception is stifled. The more it is stifled, the more contaminated the senses become. This creates disorder in the world, and that is the greatest evil of all. Polish the heart, free the six senses and let them function without obstruction, and your entire body and soul will glow.

Morihei Ueshiba, The Art of Peace

For on hearing this, if the pupil be truly philosophic, in sympathy with the subject and worthy of it, because divinely gifted, he believes that he has been shown a marvellous pathway and that he must brace himself at once to follow it, and that life will not be worth living if he does otherwise. After this he braces both himself and him who is guiding him on the path, nor does he desist until either he has reached the goal of all his studies, or else has gained such power as to be capable of directing his own steps without the aid of the instructor. It is thus, and in this mind, that such a student lives, occupied indeed in whatever occupations he may find himself, but always beyond all else cleaving fast to philosophy and to that mode of daily life which will best make him apt to learn and of retentive mind and able to reason within himself soberly; but the mode of life which is opposite to this he continually abhors.

Plato, Letters, 7.340c-d

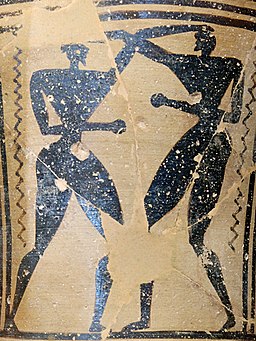

O-Sensei wrote repeatedly about “polishing the spirit” in aikido. He used several Japanese words: one was shuren, which means repetitive forging, as of a sword; other words translate “grinding” or “honing.” There are many practices in aikido that polish the spirit: I talked about the value of training last week. This week, I want to talk about the necessity of a training partner. O-Sensei did not speak of these partners as opponents; he thought of them as generously offering the resistance and friction necessary to polish the practitioner into the clearest and strongest version of themselves, the whetstone to the knife.

Plato in his later years felt similarly about the value of rhetoric. Early in his career, he was dismissive of rhetoric as a “fake art,” as bullshitting people to get what you wanted. Later, however, he came to see the value of using rhetoric to cast the pursuit of truth (philosophy) in the way best fit or suited to the person you were guiding on the path. In his letters, he talked about his struggles with the Dionysian dynasty in Syracuse: to make a very long story short, Plato saw an opportunity to guide a brilliant young tyrant into creating a version of Plato’s Republic on earth, and it blew up on him spectacularly (as schemes involving tyrants are wont to do). Plato came away from the experience with his head still on his neck (barely) and some hard-earned wisdom about how to teach philosophy (or not). Crucially, he wrote, he learned that anyone who wants to turn themselves into a true philosopher needs two things: a mentor who is willing and able to speak the truth to them (parrhēsia), no matter how uncomfortable or risky; and, a readiness to grind (tribê) day after day in the pursuit of those difficult and uncomfortable truths.

In O-Sensei’s and Plato’s writings here, we see a linked truth about the impossibility of progress without resistance, friction, and discomfort–and without a willing partner to provide it. Both aikido and rhetoric teach us that becoming our best self is in the end something we can’t do alone.

2 thoughts on “Aikido and Rhetoric: Polishing”