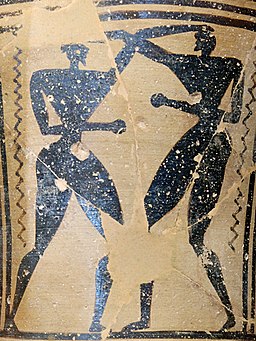

Eight forces sustain creation:

Morihei Ueshiba, The Art of Peace

Movement and stillness,

Solidification and fluidity,

Extension and contraction,

Unification and division.

What opposes unites, and the finest attunement stems from things bearing in opposite directions, and all things come about by strife.

Heraclitus, fragment 8 (Barnes)

Aikido and rhetoric are both arts specifically designed to harmonize opposition, which means that while both arts seek peace as their ultimate object, they can only generate it from conflict. This suggests to us that (a) the peace created by each art is not a static but a dynamic condition, (b) it is better understood (in English at least) as harmony rather than peace, (c) conflict is essentially a constant in life, and (d) conflict is not something to be avoided or stamped out but is rather a prerequisite of peace.

Aikido presents what is likely the easiest entry to these principles via the familiar Daoist pairing of yin and yang–negative and positive energy whose constant opposition or tension generates our sensible reality. The Greeks understood this principle via their concept of eris or strife–not strife in a pejorative sense, but as a life-drive. Just as a sprout pushes to escape its seed pod or a toddler struggles to escape her mother’s arms to walk, eris is essential to life and growth.

Both the art of rhetoric and the art of aikido cannot be practiced without an opposing partner. More importantly, the opposition offered by the partner must be clearly defined and diametric; otherwise, the joint action that emerges from the partnership will not be harmonious but a muddle of stumbles, misunderstandings, and injury. Aikido and rhetoric both teach us that being passive, not holding our ground, not being clear about what we believe, avoiding conflict–these things do not achieve peace; on the contrary, they make it impossible to achieve.