This is an essay I wrote two years ago as a thank-you to my dear friends Eric & Vicky, who gave Malena, Hyunsuk, and me their reservations for a temple-stay weekend with the Buddhist nun and chef Jeong Kwan at Baekyangsa Temple in Jeollanam-do, South Korea. LCO

“…this Body itself is Emptiness

and Emptiness itself is this Body.

This Body is not other than Emptiness

and Emptiness is not other than this Body….”

The Korean words of the chant are only distinguishable in throbs, like the vivid temple paintings of demons and patriarchs in the wavering candlelight. The rest is a harmonic drone that shivers the darkness filling Baekyangsa Temple at 5 am. It resonates in our tired bones as we stand and kneel and bow to the thrum of the Heart Sutra.

“All Buddhas in the past, present and future by practicing

the Insight that Brings Us to the Other Shore

are all capable of attaining

Authentic and Perfect Enlightenment….”

Our journey began at Yongsan station in Seoul, where Hyunsuk settled Malena and me in our KTX train seats for the ride down to Baekyangsa, plying us with Yuba choba (sweet tofu skins stuffed with rice) she had made as well as skewered, ribboned fish cakes in cups of broth she had bought at the train station. Hyunsuk is an amazing cook, and we would have been lost without her providence and guidance as we worked our way down from Seoul to the Templestay in Jeollanam-do. As the high-speed train made short work of the 250-km trip, suburbs gave way to harvested rice fields stacked with neat armload-sized sheaves ready for threshing. Traditional Korean farmhouses clustered under their swooping tiled roofs in gray or green or salmon tile, capped with dragons or white plaster finials. As far as the eye could see west, greenhouses hooped out in rows, and grandmas tended slivers of gardens they had shimmed in between their houses and the railroad tracks. Not a square inch of land lay fallow. Apartment blocks loomed out of nowhere like giants’ castles in fairy tales, 30 storeys high and 20 buildings wide, their heads in a thin pall of clouds that wore away as we headed south to reveal a tile-blue autumn sky. We wondered where all of those people worked, and then the apartments were gone just as fast as they had appeared, and we were again surrounded by fields.

As we switched from train to taxi for the last leg up to the temple, we squinted into the sunlight dancing on Jangseong Lake, famous, our cabbie said, for eel hot pot and black-raspberry wine. Baekyangsa is a major destination for fall foliage tourism, and the little town at the start of the path up to the monastery was bustling even though the leaves were nowhere near their peak. Koreans are voracious weekend hikers. They go up to the mountains in great, joyous packs, kitted out in layers of color-coordinated Gore-tex, their phones thrust ahead of them on selfie-sticks to record every second of the hike. We swerved around busloads of older Korean women moving at a gentler pace but no less impeccably turned out in full make-up and Chanel sneakers. The restaurants lining the river were named things like Autumn Delight and First Leaf Viewing Delicious Korean Specialties: I could almost taste the proprietors’ desperation as the ladies drifted by without stopping. Finishing the fiscal year in the black depends entirely on this season, and our cabbie told us the foliage peak was coming later and ending sooner each year with climate change.

Hyunsuk had been so efficient with our travel that we had a few hours to burn before we checked in at Baekyangsa, so first we sat and had coffee on the terrace of one of the river restaurants. It had colonized an old building that looked like a cut-and-paste error: part 70s brick office building, part Mediterranean villa, part art-deco opera house. Hyunsuk eyed the conglomeration dubiously through her Audrey Hepburn sunglasses as she nibbled banana chips from the ample plate of seasonal fruit—persimmons, grapes, Asian pear—that had come with our excellent coffee drinks. We had noted the groves of persimmons that studded the road from Jangseong to Baekyangsa Temple, but our jaws positively dropped at the specimens that greeted us as we walked up the forested path to the temple: these were 40 feet tall if they were an inch, the crowns of their canopies studded with orange fruit like some kind of practical joke. We rolled our suitcases past a few stands selling prayer bracelets and wooden spoons and across the old river bridge into the temple complex.

Baekyangsa claims to be one of the first Buddhist temples established in Korea, sometime in the 6th century A.D. None of the original structures remain. The oldest building in the enclosure dates from 1574; the rest were rebuilt in the 1910s after the Japanese destroyed them in retaliation for the support the monks had lent the Resistance. The reconstructed complex is lovingly maintained, tile roofs gleaming black beneath the benevolent stoney gaze of Baekamsan Peak, eaves daubed with brilliant flowers, dragons, and scenes from the life of the temple’s founder, the Venerable Yeohwan. Lush pots of chrysanthemums stud the rock gardens that frame every golden-gravel courtyard.

Baekyangsa proper is currently home to 6 monks—“or 7,” shrugs our chaperone, Jeong Yoo, when asked, as if the seventh tends to materialize and dematerialize on the whim of some arcane Buddhist magic. Jeong Yoo seu-nim (seu-nim being the honorific for a monk or nun in Seon Buddhism) is a careful and literal man, handsome with his shaven head and voluminous, stiffly pressed dove-grey linen jacket and trousers. We are in our temple uniforms now, too—much more humble ensembles of navy rayon. The temple tour Jeong Yoo is giving us isn’t going well. At our first stop, the Gate of the Four Heavenly Kings, he has stuttered to a halt because a saxophone ensemble below us is blaring “Phantom of the Opera.” “They’re from the local church,” he finally comments with just a wrinkle of ire creasing his serene brow. He starts telling us about the recent escalation of antagonism against Buddhist establishments by Korean Protestant churches. But then he seems to think better of this line of argument and stops himself with a soft, “That is irrelevant.” The Four Heavenly Kings appear to disagree: they glower down at the saxophones as if they aim to crush them along with the carven sinners and demons grimacing out from beneath their gargantuan wooden sandals.

In the early evening, we gather at the temple bell tower and walk up the river about a third of a mile to the tiny temple compound that Jeong Kwan shares with two other nuns. A white dog with an curly tail barks ferociously at us from the lower garden—Buddhist pest control. As we pick our way through some construction down to the classroom that has been newly built onto Jeong Kwan’s kitchen (both temples are being renovated and expanded to accommodate the surge of guests that have arrived in the wake of the Chef’s Table episode), it takes us a moment to realize that the chef has folded herself in with our group. Her eyes gleam mischievously, and she beams under her stocking cap. She wears a sweater over her nun’s habit and swings a smart phone in one hand.

Inside, she leaves us to stand behind the counter of her demonstration kitchen with its induction range, pendant lights ingeniously upcycled from broken vinegar jars, and exposed shelves supporting teetering stacks of gorgeous black and white ceramics. The 24 of us file in to sit at two long tables of 12 each. Pitchers of lotus tea and bowls of mandarins are set before us, and Jeong Kwan, working through an interpreter, has us go around and introduce ourselves. There are people from Manchester and Singapore and Spain, from several places in the U.S. and from London. As the introductions conclude and Jeong Kwan busies herself setting up her station, Hyunsuk starts grilling the good-looking Korean-American kid with the expensive watch sitting across from us: she is on the lookout for a good match for her daughter Jeewon, who, to her mother’s chagrin, currently seems more interested in ceramics than in men (she’s just finishing an Art MA at the prestigious Seoul National University). Brian, for his part, burned out of Operations at Amazon—after having, you know, designed Whole Foods’ home delivery system—and is taking sixth months to travel around the world. This particular leg of his Grand Tour links Baekyangsa to a visit to his family’s estate in Jang-eup to pay his respects at his grandfather’s grave. The gleam in Hyunsuk’s eye is brighter than the pendants swinging above Jeong Kwan. By the time we’ve left the temple, she has extracted a promise from Brian to email her, on the pretext of getting a copy of the picture she made him take with his camera of the three of us standing on the temple bridge.

Our class session begins with a lecture from Jeong Kwan on the Buddhist principles behind her cooking. She talks about the beings that make up her mountain home: human, animal, plant, and stone. She talks about the four elements that circulate among all of these beings and bind them together: earth, sun, water, and wind. She relates these elements to human flourishing in the form of bone, body heat, blood, and emotion—and also to the four seasons. This base-four logic is a unique feature of Seon Buddhism, which sought to unify what were seen as inconsistencies in Buddhist doctrines inherited from China and elsewhere.

As she speaks, the interanimations multiply, tracing a four-part mandala of dizzying complexity in my head. And then she distills it all into a king trumpet mushroom. She holds it up in front of us and says her job is to bring out the essential being of this mushroom by the techniques of braising, drying, fermentation, and seasoning so that it will nourish her and the people she cooks for to its maximum potential. She takes the mushroom, cuts it into thick, square slices, and sets them braising in a court bouillon of water, soy sauce, and perilla seed oil. Then, she turns her attention to some fat zucchini rounds that she has sliced and partially scooped. She takes a block of fresh tofu, tears off a handful, and begins squeezing the water out of it as she says that when she cooks with processed foods like tofu or dried fruit, she tries to return them as much as she can to their original state—either by removing or adding water. She chops a brunoise of fresh chiles and adds this to the tofu, then sets some of our fellow classmates to the task of stuffing the zucchini rounds for her. When a guy name Cain hands his tray back to her, she teases him as she smoothes his craggy scoops: “We eat with all our senses, not just our tongues,” she says. “Food must be beautiful to fill us.” The remaining stuffers hurriedly bend to redress their efforts, and as they hand in their work, Jeong Kwan picks up her smart phone, grinning impishly, and takes pictures of her new disciples with their handiwork.

The mushrooms are almost done. She glazes them with a brown rice syrup that she makes herself out in her jang dokdae, or “fermentation garden” of giant brown stoneware jars crowded onto the roof of a low building just outside. They cradle the potions that compose the steady bass line on which Jeong Kwan improvises the seasonal counterpoint of her cookery. She talks about this process of composition as one taking place in slow time. Soybeans, for example: in the first year, fresh beans are salted to draw off their moisture; in the second, the resulting stew is ground, fermented, and strained off to make soy sauce; in the third, the strained solids are fermented again to make doenjang. The tray in front of her holds both these condiments as well as the rice syrup, salt, black raspberry syrup, sesame oil, and perilla oil. With these condiments alone, accompanied by various spices and herbs, she generates myriad seasoning profiles that lend her dishes not only layers of flavor and texture, but crucial nutrients. Jeong Yoo will tell us the next day that monks who keep to a strictly vegan diet are at risk of serious nutritional deficiencies and diseases after several years—unless they devote themselves full time to the slow crafting of nourishment in the way that Jeong Kwan has.

The zucchini are finished steaming now, and Jeong Kwan plates them on a beautiful blue-and-white platter. She stops mid-sentence to step out into the gloaming with a pair of scissors in hand, coming back with a handful of perilla leaves and blossoms. These she nestles in one corner of a large, white rectangular dish, layering over them mushroom slices like the scales of a barky stump whose top the perilla seeds have sunk into and bloomed out of. She finishes the plating with a mossy scattering of green chile slivers.

One dish remains: Jeong Kwan squeezes water from handsful of a long, steamed green “mountain vegetable” that looks a bit like Chinese kong xin tsai. She mounds the greens in a bowl and begins massaging in a paste made from doenjang, ginger, black raspberry syrup, brown rice syrup, sesame seeds, and the rest of the pepper brunoise. As she works, she comments that in Korean there is an expression that homecooked food tastes like “mother’s hands,” but this means the delicate fingers, not the palm, which transfers too much heat and force into the food.

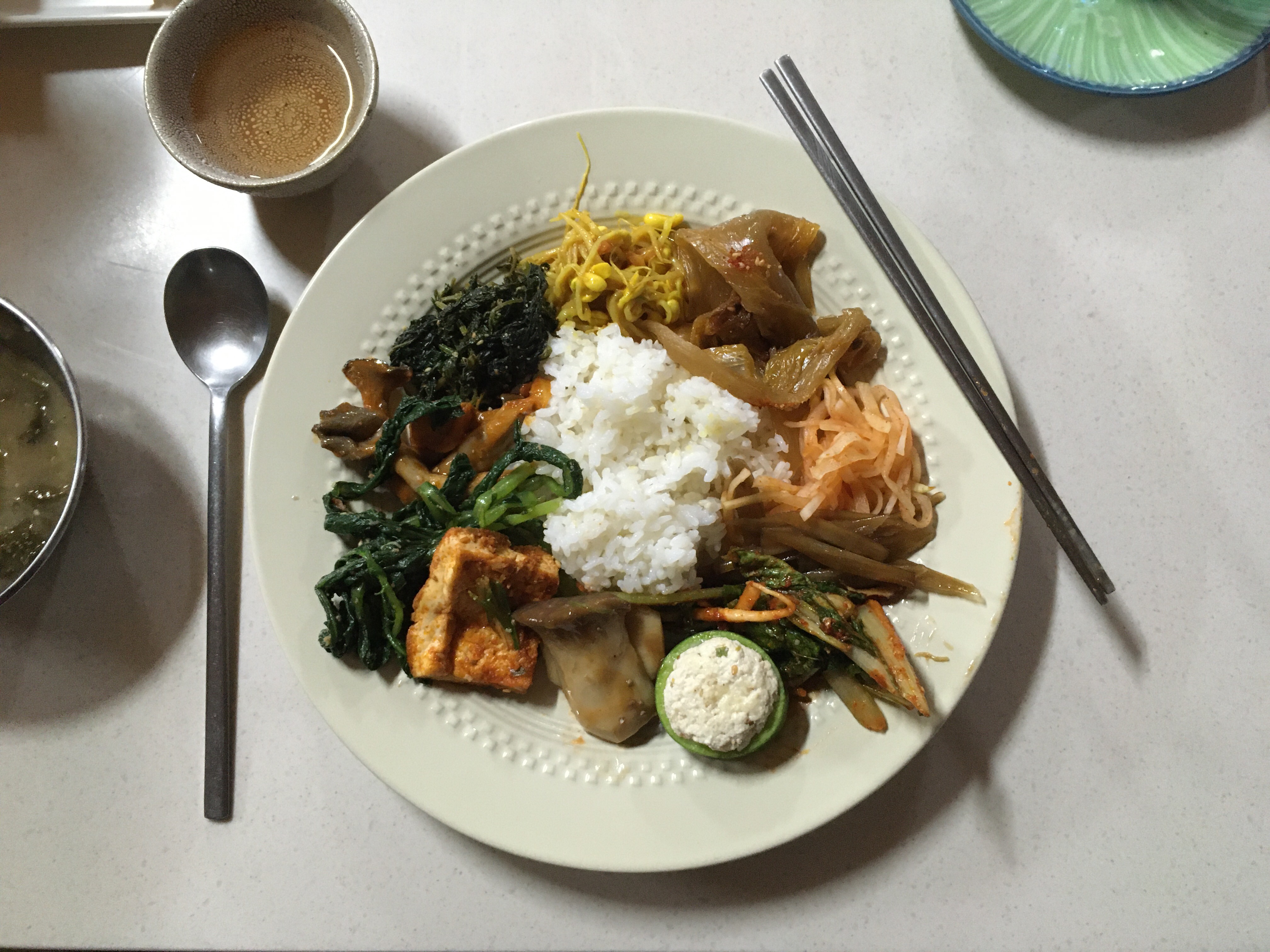

These dishes complete, Jeong Kwan invites us into her traditional kitchen next door, where the three platters she has assembled are laid out on a long wooden table with other dishes made by her assistants. The kitchen is my ideal of a kitchen: everything low, rough, and relentlessly practical, with an enormous iron wok set over an open charcoal fire pit, a huge fruitwood cabinet whose grain has mellowed over a hundred years or more, ranks of gorgeous, fat ceramic jars glazed glossy black, and pegs hung with gourds and grass brooms for scooping and cleaning. The walls are plastered a warm terracotta. We circle round the table and fill our plates then go back to our stools to eat.

The flavors and textures are subtle, as hard to pick up on a Western palate accustomed to being titillated with spice, fat, and sugar as the opening notes of Górecki’s Symphony #3. Jeong Kwan has instructed us to chew slowly to fully realize the flavor profile, and she is right: the layers she has built into the mushrooms unfold like a fan as I concentrate on each pleat: silk, sugar, wood, perfume, heat. I realize with a shock how much of the experience of eating I am missing as a fast eater. Still, though, my favorite dish is the one that Hyunsuk declares with a frown to be too salty—fresh green stems macerated in vinegar, ginger, chiles, and flowers. The resulting flavor patterns woven by these four elements are so complex they escape into the realm of the sublime, like the polychords of a Gaelic psalm. I feel joyful as they wash over me, unanalyzed.

As we finish with ripe persimmons for dessert, Jeong Kwan says she will take questions. I ask her about the role of perfection in cooking. I have been thinking a lot about perfection lately: in work, in relationships, in art. Jeong Kwan nods and stares straight ahead for a breath or two. Then, she speaks for five straight minutes, entirely in Korean of course; still, the way she looks at us and the way she gestures—pulling her arms in strongly toward her chest one moment and then pushing them out toward us the next, knife-scarred fingers splayed wide—I know what she is saying even before the translator begins to speak. I know she is saying that cooking is communication and so perfection is communion, the cook and the eater being present to each other through the meal in a way they were not and could not be before. The translator adds to this awareness Jeong Kwan’s belief that her techniques all drive toward knowing and bringing out the essence of the plants she works with, and knowing and bringing out the essence of the people she cooks for, and bringing these together. This kind of communion is called nutrition, of course, but it is something more as well. It is shared pleasure and sensation and joy. It is compassion. It seems to be something like what rhetorician Kenneth Burke called consubstantiation, when two people by communicating become a community, when they become substantially one through the sharing of a mindset. This seems close to the heart of Jeong Kwan’s calling as a Buddhist and as a chef, and, importantly, it is the calling that is perfection, not its accomplishment, if there even is such a thing. Perfection for her is dynamic. It lives in the work, not the result.

Jeong Yoo wakes us in the starry dark of 4:45 am to join the monks for the morning ritual. As we shuffle up to the main temple, the big bell bongs with a gentleness that seems out of keeping with its mission of shaking sinners in hell out of their attachments to the world.

After the morning ritual comes breakfast in the main temple dining hall. The vegan dishes spread out beside the giant steamer full of rice—kimchi, mushrooms, tofu, greens—are plentiful and delicious. The rule is you can go back as many times as you like but must finish everything on your plate. Another rule is that you cannot start eating until the monks have begun, and a Dutch member of our cohort who missed that memo receives a sharp correction from Jeong Yoo. When the breakfast dishes are washed—by us, another rule—Jeong Yoo takes us out, puts a windswept-looking bamboo broom in each of our hands, and sets us to brushing the fallen leaves out of all the pale granite courtyards. It’s cold out, so we sweep briskly, and it’s amazing how quickly we canvas the roughly two-acre main compound. Lina and Dawson, two Americans who met while she was teaching English in Singapore and he was stationed there with Army logistics, make a sort of Zen garden out of a circular bit of courtyard between the bridge and the Gate of the Four Heavenly kings. Here various games are set out for children—like old kimchi jars to toss sticks into—and vendors are setting up their stands for the day, selling ginseng, roasted chestnuts, ginger tea, and prayer beads. I have my eye on the chestnuts, but first, a hike.

Under the enthusiastic direction of Daisy, our templestay coordinator in the front office just inside the Gate, we choose a trail that winds up eventually to Baekamsan Peak. Our destination, however, falls quite a bit short of the summit—a little hermitage, Yaksaam, and the cave spring just beyond it. The trail is already buzzing with hikers. They greet us with a cheerful “Anyung haseyo!” and when I reply, they laugh in surprise and joy, eyes sparkling as if a parrot or puppy has just started talking to them. After establishing the rather meager limits of my Korean, they wave an indulgent goodbye and puff on up the steep trail. It’s so steep, in fact, more like a staircase, that there are many more opportunities for intercultural conversation as we all lean on trees and pant in the leaf-dappled autumn sunshine. On one of these rests I turn over in my fingers an acorn with a delightfully spiky top like a chestnut. A man sees me squinting at it and says, “Sansori! Sansori!” Someone else corrects him: “Tottori!” and he shakes his head and shows me by pantomiming with his hands that the tottori acorn is longer and narrower. Hyunsuk chuckles as he heads down the trail with his wife and whispers to us that his wife is chiding him, “Who cares! It’s an acorn! You’re always telling people things they don’t care about!” But I do care—because I have never seen a furry acorn before, and because kindness means a lot to me these days.

We reach Yaksaam as the monks are beginning a ceremony for a group of visitors. We pass on, buoyed by their chanting up the last flight of stone steps to the cave spring. A platform has been built into the cave opening so that the top half arches into a stalactite-laced shrine under which a bodhisattva presides over a small, airy meditation space. The bottom half shelters the spring. Hyunsuk fills a plastic dipper from the dark, cool pool and hands it to me. I drink. The water tastes like nothing in the best way. Or perhaps it tastes like stone. I think of what Jeong Yoo said about caves, too, being beings, and I wonder if she would consider this crystalline water its blood.

At lunch, nibbling on our dessert of black-bean mochi cakes and solomon’s seal tea, we ponder how to pass the several hours before our train leaves from Jangseong station. Hyunsuk’s eyes light, and she hurries over to the office to ask Daisy some questions. She comes back with a plan, and a half hour later we are piled into a taxi with our bags, heading up and over a neighboring pass toward Gochang Hot Springs Resort, a Korean public bath attached to a hotel. Hyunsuk has the driver laughing not even a quarter mile into our trip. Her charisma is viral. I literally do not remember a single person we encounter on the trip reacting to her rapid-fire queries and lively machinations with anything short of delight: monks bring us extra tea bags, kitchen staff suddenly produce a plate of cake left over from a memorial service, Brian snaps our picture with his fancy Fuji camera, tired-eyed women at reception desks flush pink as they chatter animatedly…. I realize as I listen to her talk with the taxi driver that Hyunsuk is an artist, too, achieving with her smile and her warm, low voice the same thing that Jeong Kwan achieves with her cooking.

On weekends everyone goes to jimjilbang like the one at Gochang. The spas are segregated by gender, and so everyone on our side is naked. Women and girls of all ages, sizes, and shapes float tranquilly in pools labeled with various temperatures, appear and disappear in puffs of steam from the sauna, get slapped with loofah sponges by burly masseuses, and squint into the warm autumn sun and gossip with friends as they sip from the thermoses of rejuvenating broth or tea they have brought with them. Golden earrings jangle, red lips flash, eyes sparkle, and a week’s worth of fatigue and worry swirls down the drains in the tile floor. I remember what Jeong Kwan said about perfection and think, this is it, too.

At Hyunsuk’s cozy apartment in Daejeon, she prepares a delicious beef bulgogi with homemade kimchi, and we make it through the better part of a bottle of red tempranillo—her Korean friends are besotted with Spain and Spanish wines at the moment. For dessert she pours us some of the black raspberry wine she picked up in Gochang, and we talk about work, children, God, food, death, love. The taste of the berry wine lingering on my tongue is the taste of all of those things and also of maples just turning red at the tips, of the icy, clear water of the cave spring, of electric-green ferns edging shyly out between black roof tiles, of candle flames, of the dark tones of a bell meant to wake the dead, of girls in gold bracelets holding hands and spinning, laughing in steaming springs.

Too soon we are hugging Hyunsuk goodbye and then taking the express train to the airport, settling as best we can into our Procrustean seats and deciding which terrible movies will numb the 10-hour flight back to LAX. But trips either end too soon or not soon enough, and I’ll take the too soon, I think. As we fly over Japan I am full of ideas about finally becoming something more than a terrible gardener, growing my own food, cooking for friends, chewing more slowly, having as much compassion for myself as I have for others. But I am also full of fears that, just like the taste of the black raspberry wine, it will all fade, and I’ll forget, and I’ll be right back to rushing through my life thinking I’m doing it all wrong.

To distract myself from these uplifting ruminations, I ask Malena what stood out to her from the trip. She says Jeong Kwan’s answer to my question about perfection, and also Jeong Yoo’s answer to Malena’s question about how to get better at meditation. “I liked how he said you just have to stick with it, that’s how you get better,” she says. “Some of the stuff he does, I can probably never do. But I can stick with it. That I can do.”

I look out the window and see Mt. Fuji, actually see it, streaked with tears of snow, towering above the clouds so high I swear we would fly right into it if we were headed that way. I think of a line from Sorley Maclean’s poem, “The Cuillin,” where he takes hope from the “watchful, heroic” mountain as he sees it “rising on the other side of sorrow.” I think of my friendship with Malena, which has both rooted us and held our heads high above the storms of our lives for 33 years and counting. I think of my friendship with Hyunsuk, which has spanned two continents and the loss of fathers and husbands both. I think of the joyous clan of women who come to Gochang Hot Springs every Sunday without fail to take care of themselves and each other. I touch the beads of the little red prayer bracelet Jeong Kwan gave each of us at the end of our evening together. And I think, I can stick with it. There’s a lot I can’t do. But I can do that.

4 thoughts on “Perfection”